Ironcladding

Answering the best version of someone's position

Hello Gorgias! is a weekly newsletter devoted to writing, rhetoric, and long-form argument. If you’re enjoying my posts, please consider becoming a subscriber.

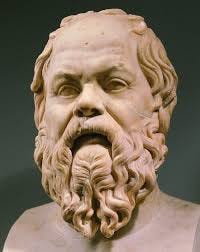

For the last few weeks, I’ve been examining the debate between the philosopher Socrates and the rhetorician Gorgias, as depicted in Plato’s dialogue of the same name.

Socrates comes down hard on rhetoricians. He describes rhetoric as a species of deceptive flattery that succeeds by telling audiences what they want to hear instead of telling them the truth.

Plato’s critique of rhetoric was so effective, rhetoricians are still responding to it. Every response is different but, according to the rhetorician Richard A. Lanham, they generally fall into two camps:

The “Weak Defense” of rhetoric posits that rhetoric is a neutral tool that can be used to accomplish good or evil. Furthermore, anyone who hasn’t mastered rhetoric is at the mercy of anyone who has. This is the argument Gorgias tries (and fails) to defend.

The “Strong Defense” of rhetoric posits that the truth always emerges in a social context. It’s discovered, negotiated, and shaped at the level of discourse. It needs to be successfully communicated to have any effect. This means rhetoric is generative and creative; it’s essential to establishing the truth.

Briefly put, the “Weak Defense” of rhetoric claims that rhetoric needs philosophy because philosophy provides the moral foundation rhetoric lacks. The “Strong Defense” of rhetoric claims that philosophy needs rhetoric because even the most objective truths are socially mediated.

You don’t need to choose between the “Weak” and “Strong Defense” of rhetoric. They aren’t mutually exclusive. Rhetoric can be misused. Truth is determined in social contexts.

Philosophy needs rhetoric. Rhetoric needs philosophy.

Plato knows this. Socrates demolishes the “Weak Defense” of rhetoric, but his dialectical method, attention to audience, and skillful ability to dictate the terms of his debate with Gorgias implicitly endorse the “Strong Defense.”

By portraying Socrates as a brilliant rhetorician who doesn’t need to try very hard to beat Gorgias at his own game, Plato demonstrates the value and necessity of persuasion. Socrates claims rhetoric is flattery, but the way the text is actually written presents a strong argument for combining rhetoric with philosophy.

In the rest of this post, I’ll describe how to combine rhetoric and philosophy by applying a technique called “ironclading” to an opponent’s argument to capture the benefits of both.

Ironclading an Argument

A straw man fallacy is when someone constructs a watered-down version of an opponent’s argument and responds to that instead of what their opponent is actually saying.

Ironclading (sometimes called steelmanning) is the exact opposite. You’re responding to an “ironclad” version of your opponent’s argument even when your opponent hasn’t articulated that position.

There are two reasons for adopting this practice in your writing. The first is ethical. The second is pragmatic.

The ethical indictment of the straw man fallacy is self-evident. It’s deceptive and manipulative. The speaker who uses the straw man fallacy is not being fair or honest. In contrast, a person who “ironclads” an opponent’s argument has committed to arguing in good faith.

But there’s also a pragmatic reason for ironclading your opponent’s argument. It subjects your position to a series of rigorous stress tests that strengthens your argument in the long run. You can better anticipate and preempt rebuttals. And unlike the straw man fallacy, which only works until the audience catches on, ironclading establishes your credibility with audiences by demonstrating that you have a better grasp of the topic.

Remember, Socrates’ critique of rhetoric is effective because he understands rhetoric better than Gorgias does.

All of this sounds easy, but it’s not. Most people have a hard time identifying the strongest version of their opponent’s argument because:

People tend to equate being wrong with being stupid. We’ve all been wrong before, so we know this isn’t true. But when we get into arguments, we act as though it is. When we’re firmly committed to our position or offended by someone else’s argument, we’re even more inclined to do this. In Gorgias, for example, Socrates succeeds in provoking Polus’ incredulity and immediately seizes the upper hand.

People mistakenly assume the strength of an argument is determined objectively. But the most strongest argument is always the one the audience finds most persuasive. This is why fact-checking conspiracy theorists online is an exercise in futility. It doesn’t matter how “good” the argument is because the target audience will never accept the message.

Put differently, people are generally bad at ironclading because they assume that “being right” and “being persuasive” are generally the same thing.

Fortunately, we can learn from Socrates. We can embrace methods and methodological assumptions that challenge our natural tendency to dismiss arguments we disagree with. We can play the Believing Game, for instance, or learn to respond to the strongest version of arguments we disagree with by taking the following steps:

Commit to fully immersing yourself in the thing you’re critiquing. Full immersion is necessary because your opponent’s strongest argument isn’t always the most popular or well-known argument. Moreover, the difference between shallow criticism and a robust critique is the level of good faith engagement with the position you’re challenging. You don’t need to read the Bible to be an atheist, but you’d better be able to recite scripture if you want to convince other people to become atheists.

Remind yourself that you’re probably wrong about something. It’s a statistical inevitability. Keeping this in mind helps you identify the weaknesses in your position and gives you the ability to make strategic concessions that advance your long-term goals.

Assume the other person knows more about the topic than you, even if they don’t. A healthy dose of humility never hurt anyone. Additionally, folks who acknowledge the limits of their own knowledge are better positioned to ask smart questions.

Assume the audience is sympathetic to the other side. Just because you think you’re right doesn’t mean the audience agrees with you. I call this the “activist fallacy,” because people who believe they’re on the “right side of history” have less incentive to persuade everyone who disagrees with them

Keep in mind that it’s not enough to understand the argument you’re refuting. You also have to understand how specific experiences, relationships, or commitments make an audience inclined to accept the argument. It all comes back to knowing your audience.

Good luck with your writing!