Hello Gorgias! is a weekly newsletter devoted to writing, rhetoric, and long-form argument. If you’re enjoying my posts, please consider becoming a subscriber:

If you’ve had to take a speech or communication class, you’re already familiar with the rhetorical triangle — three modes of persuasion (ethos, pathos, and logos) typically associated with Aristotle.

Generally, logos refers to the persuasive qualities of logic and rationality. Ethos is the appeal of a speaker’s character or reputation, while pathos is any attempt to reach an audience by way of their emotions.

But is that really all there is to it? Personally, I don’t think so.

When we’re talking about strategies for connecting with an audience, the rhetorical triangle is a great place to start. But it’s not the end-all-be-all-of persuasion. There are other dimensions of persuasion that the rhetorical triangle doesn’t account for.

In today’s post, I’m going to briefly touch on all three corners of the rhetorical triangle. This will help highlight something that gets left out of these discussions — namely, kairos, the concept of timing or opportunity.

Logos

When we use the word logos, we’re generally talking about appeals grounded in logic or rationality. Logos encompasses everything we typically associate with the Cartesian subject, including our ability to make calculated decisions based on available information and enlightened self-interest.

In conversations about logos, it’s important to clarify that logos is not the same thing as “being objective.”1 For Aristotle in particular, logos often refers to the logical consistency of claims — does the syllogism make sense? Can the audience infer the missing premise of the enthymeme?

That said, I also think it’s fair to argue that logos would include things like reflection, critical thinking, and the ability to weigh the potential consequences of competing actions.

Ethos

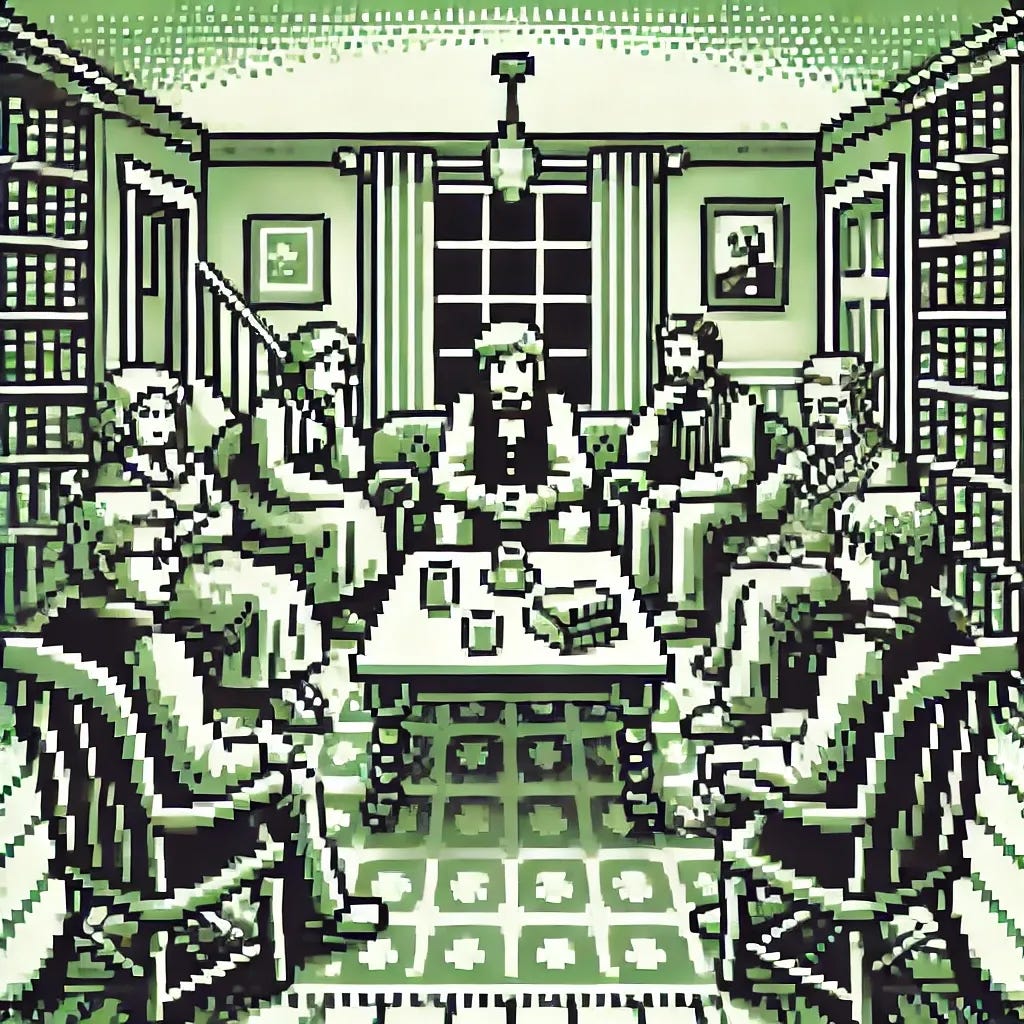

Ethos is often used to describe appeals based on character, but I think Kenneth Burke’s parlor metaphor gives us a more specific way to think about ethos.

Imagine you’re sitting in Burke’s parlor, watching the discussion unfold around you. As an observer, you’d inevitably notice that some people are better parlor guests than others. Some folks are polite and respectful. They always support what they’re saying with evidence and make an effort to include others in the conversation. Others are more hostile and antagonistic. They offer uninformed opinions and do not meet the burden of rejoinder.

As the conversation got more heated, you’d learn more about these “bad guests” from their own actions. You’d also hear about them from other folks in the parlor. And you’d form an impression based on these conversations and observations.

If you decide someone in the parlor just likes getting people riled up, or isn’t interested in the evidence, you’d be less likely to go along with what they’re saying. Alternatively, if someone develops a reputation for speaking honestly, other folks in the parlor will be more willing to give them the benefit of the doubt.

In other words, ethos is an umbrella term for persuasive strategies that rely on someone’s standing and reputation in the parlor.

Pathos

Broadly speaking, pathos includes any appeal to emotions. This could involve humanizing or personalizing a situation to persuade an audience to act, but it could also include using music, lighting, or colors to influence an audience’s mood.

For me, pathos ends up being something of a “catch-all concept” that includes everything that doesn’t quite fit into the other two categories. The best example of this is pleasure. For Aristotle, emotions are persuasive because they appeal to pleasure. But he’s also assuming that pain and pleasure are mutually exclusive.

What about people who seem to get pleasure from specific forms of physical or emotional pain? What about people who pursue pleasure compulsively, until it becomes painful? Aristotle denies these situations are even possible, which means he’d likely struggle to explain how something like grievance politics (which involves both pleasure and pain) could be persuasive.

Kairos

As much as I love the rhetorical triangle, it does not address the persuasive qualities of context itself. That’s why there’s a fourth term that frequently comes up in conversations about persuasion: kairos, a Greek word that emphasizes time in a qualitative sense.

Kairos is the idea that there is an “ideal” or “right” time for action. The word comes from the Greek god Caerus, the god of luck and opportunity. He has wings on his feet, like Hermes, and is always depicted as fleeting. He has a single lock of hair flowing from the front of his head. The back of his head is completely bald. The idea is that if you want to seize opportunity, you have to do it head on. Once opportunity has passed you by, there’s no way to capture it again.

In rhetorical theory, kairos is a way of accounting for things that are persuasive because they occur in the right place or at the right time.

Conclusion

Ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos are not distinct categories. There’s a lot of overlap and exchange. Additionally, writers can (and d) adopt more than one of these modes at the same time. I can write an argument that is logical, moving, credible, and aligned with favorable circumstances.

At the same time, having four distinct categories can be useful. It introduces the possibility of presenting the same argument in four different registers, according to the context and the audience.

We should never limit ourselves to the rhetorical triangle by assuming there are only three modes of persuasion. We also have to consider how things like timing, context, and the subject’s desire for satisfaction (jouissance) shapes which claims an audience is willing to accept as true.

Ancient rhetoricians did not understand the subject/object distinction the same way we do.